The indigenous language dictionaries of Russia

About this exhibit | Languages | Language Dictionaries | Useful Resources

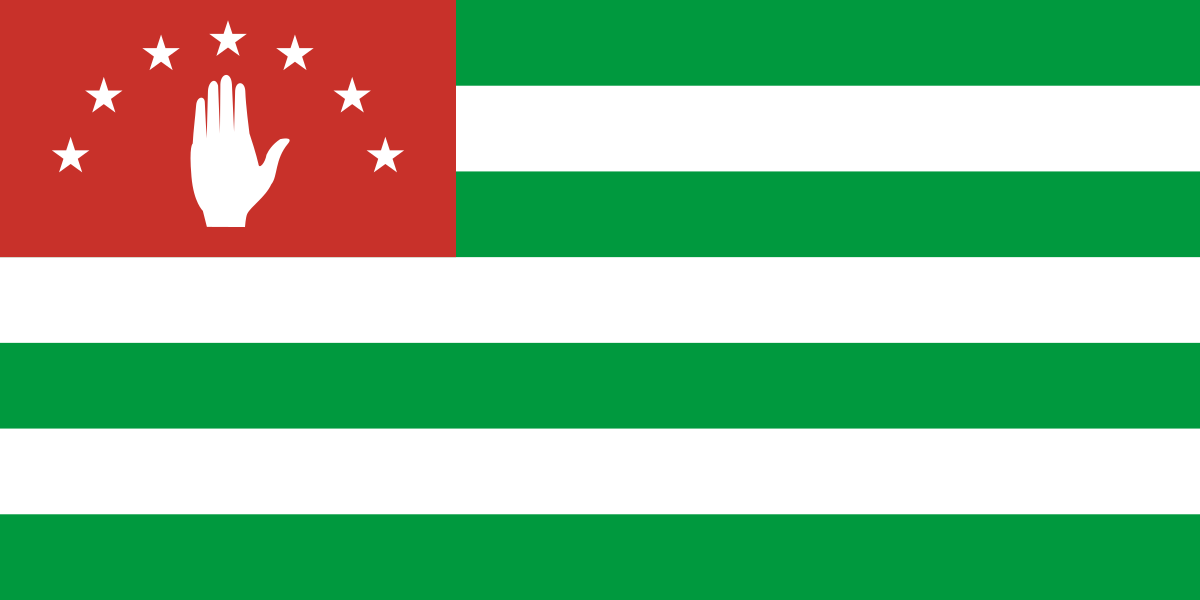

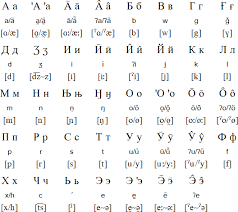

Russia’s multinationalness is widely recognized and celebrated, so is its multilingualism. Russia is linguistically among the most–perhaps after Nigeria, India, China, Brazil, the United States, and a few others–diverse countries of the world. With its dominant national language, Russian, at the forefront, it is home to around 170 different languages, according to the official 2010 national census summaries.

These languages vary from one another in the user population, development, official status, or continued viability. For example, if Russian as the state language of Russia is spoken by about 96% of the whole population, Negidal, an indigenous language spoken in Eastern Siberia near Khabarovsk, had only 74 speakers at the time of the 2010 census and is now considered to be “moribund.” (Ethnologue) If not as dire as that of Negidal, and if also right away excluding such robust ones as Tatar, Bashkir (or Bashkort), Iakut, or Buriat, the overall state of Russia’s indigenous languages–about 100 of them identifiable in the 2010 census—might as well be characterized as less than envious.

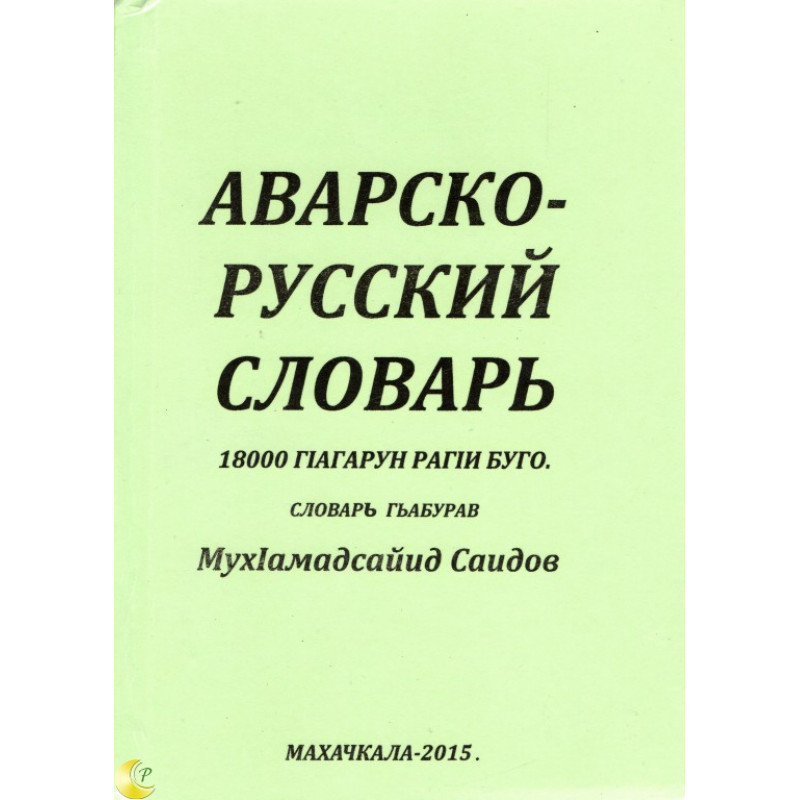

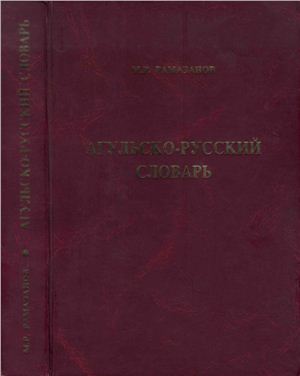

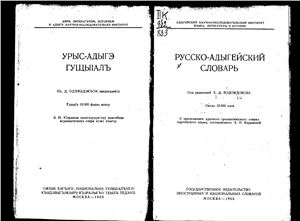

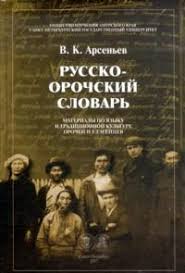

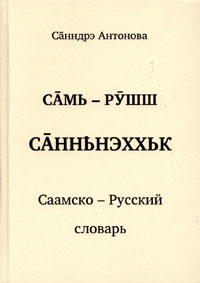

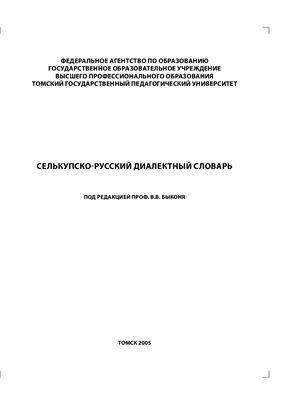

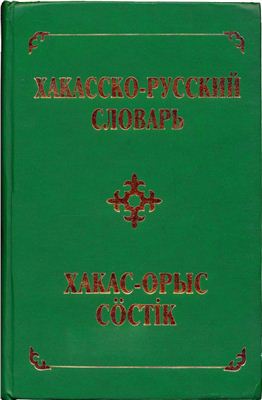

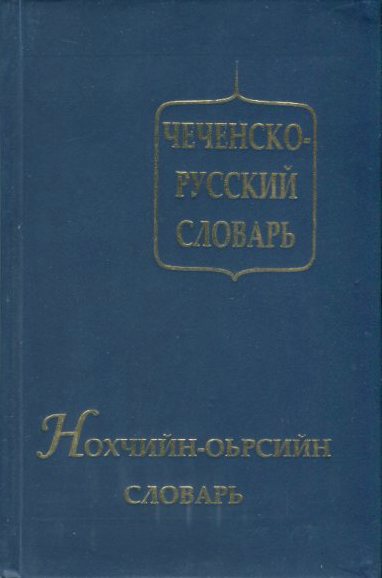

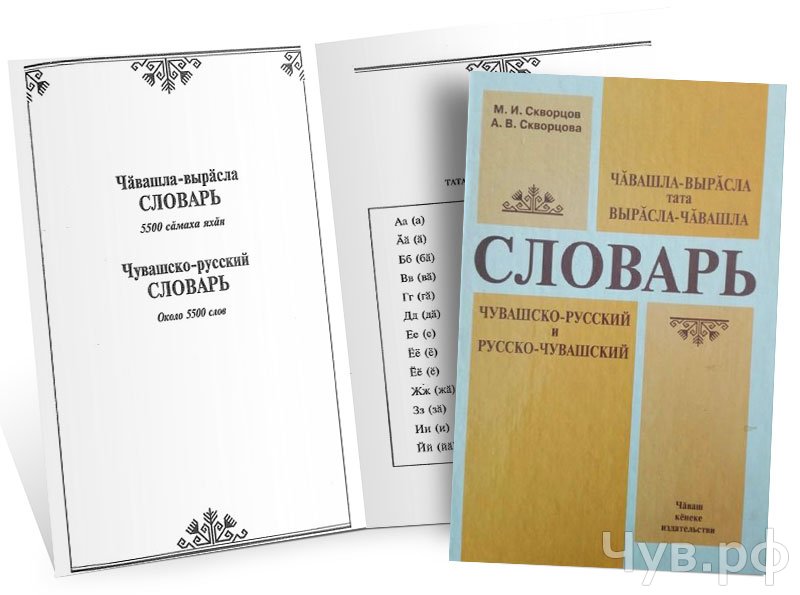

This exhibit presents about 60 language dictionaries and grammars, all germane to Russia’s indigenous languages and accessible in print in the Herman B Wells Library of Indiana University. With one sole exception, they are all Russian or Soviet imprints published in many different locations including Moscow and St. Petersburg, the two publishing powerhouses of Russia. In this exhibit no language is represented more than once, which reflects its main intention: to put on view as many languages as possible. Encountering this many indigenous languages of Russia in one place through published language resources is likely to be a rare experience for most of us, and that was in fact the idea behind the making of this exhibit. This installation, though modest, will hopefully help its visitors get more familiar with these languages and reimagine their multifaceted cultural significance as well.

Credit: Emma Patterson, student assistant for the Slavic and East European Studies Collection, 2019-2020, for her critical contributions to designing and assembling this exhibit.

Buriat

Buriat

Endangered languages of indigenous peoples of Siberia

Ethnologue: Languages of the world

Ethnologue: Languages of Russian Federation. (23rd ed. 2020. Available for IU users in full text online in Ethnologue)

Iazyki i kul’tura narodov Rossii

Iazyki narodov SSSR. 5 vols. 1966-68.

Iazyki Rossii (Institut iazykoznaniia RAN)

Materialy dlia izucheniia evenkiiskogo iazyka

OLAC (Open language archives community)

Ságastallamin – Telling the story of Arctic Indigenous languages [an exhibition]